- FOR

Sarah Scout Presents

- URL

http://www.sarahscoutpresents.com/

Prints and Paintings from Veronica’s solo practice.

Veronica is represented by Sarah Scout Presents

http://www.sarahscoutpresents.com/

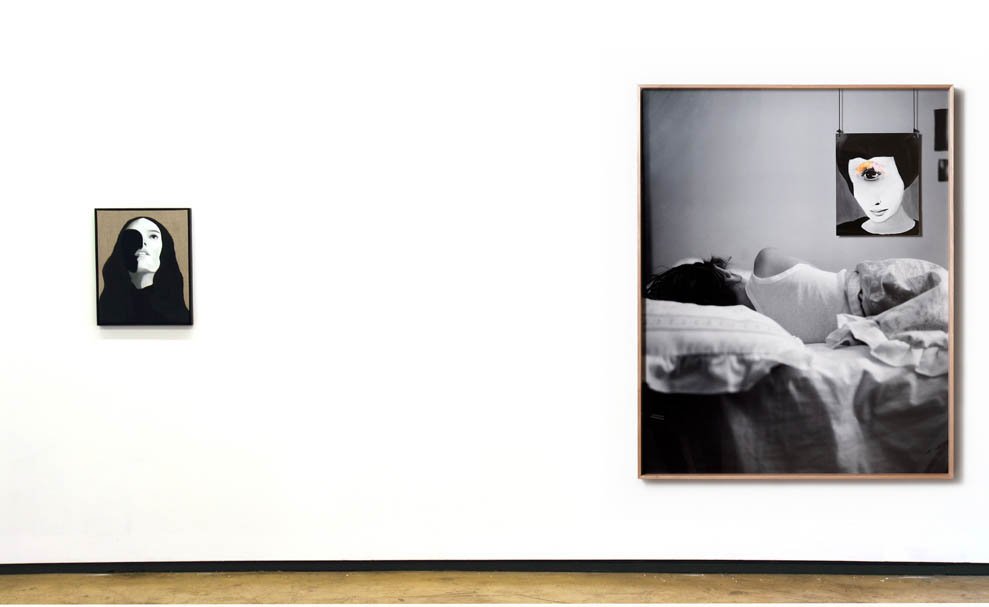

Innocence and Experience

written by Anusha Kenny for ‘Ode to Form’ curated by Kelly Fliedner at WestSpace.

http://odetoform.info/about/

First published in 1789, William Blake’s illuminated manuscript Songs of Innocence and of Experience: Shewing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul, sets forth a set of relationships and tensions between the twin states of “innocence” and “experience”. The world of “experience” is the world adults live in when they are awake. It is a big world, filled with sadness and fears. Sick flowers, wild animals, dark forests, and prematurely embittered children haunt the passages. Nevertheless, it has its own internal logic, and any changes that take place in this world are, on the whole, orderly and predictable ones. This order is assured by the adults’ submission to ‘law’, and so the world in Songs of Experience is made up of law-abiding adults who ignore their errant desires.

But adults weren’t always like this. When they were children, happiness was based not on law, but on love, play, and exploration. In the world of Songs of Innocence, infancy is aligned with pre-social, unconscious joy. But this is a joy that only survives because of the adults who protect and nurture the infant, holding them, providing for them, and watching them sleep. Thus, for Blake, the state of “innocence” is an illusion that survives only because there are vigilant parental figures around the cherubs and lambs to fend off the dangers and wolves lurking at the edges of each colour plate and stanza.

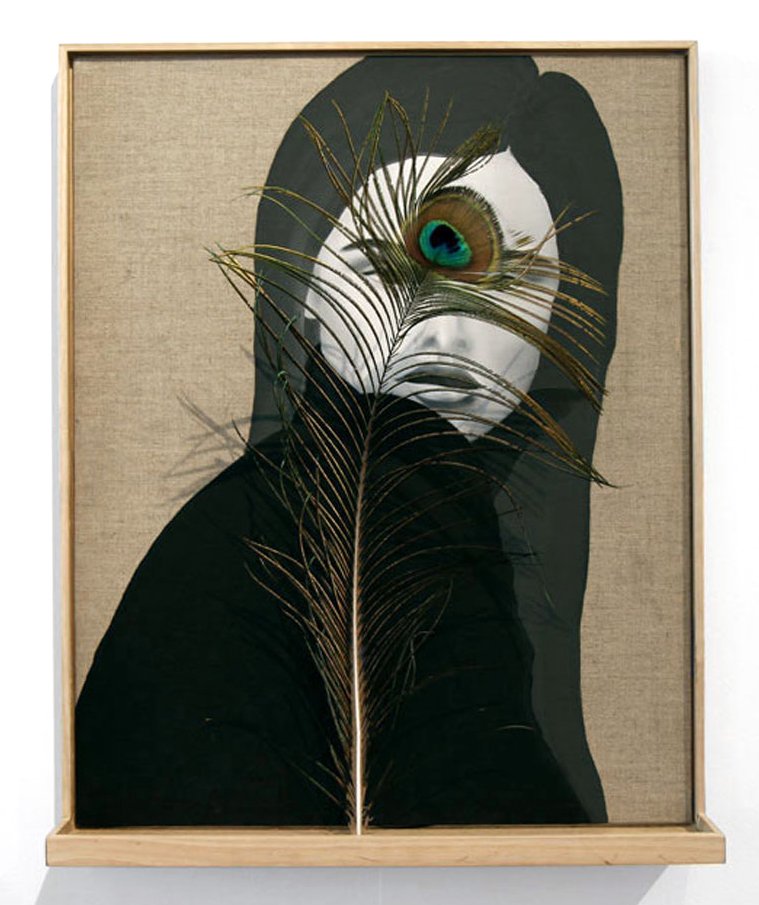

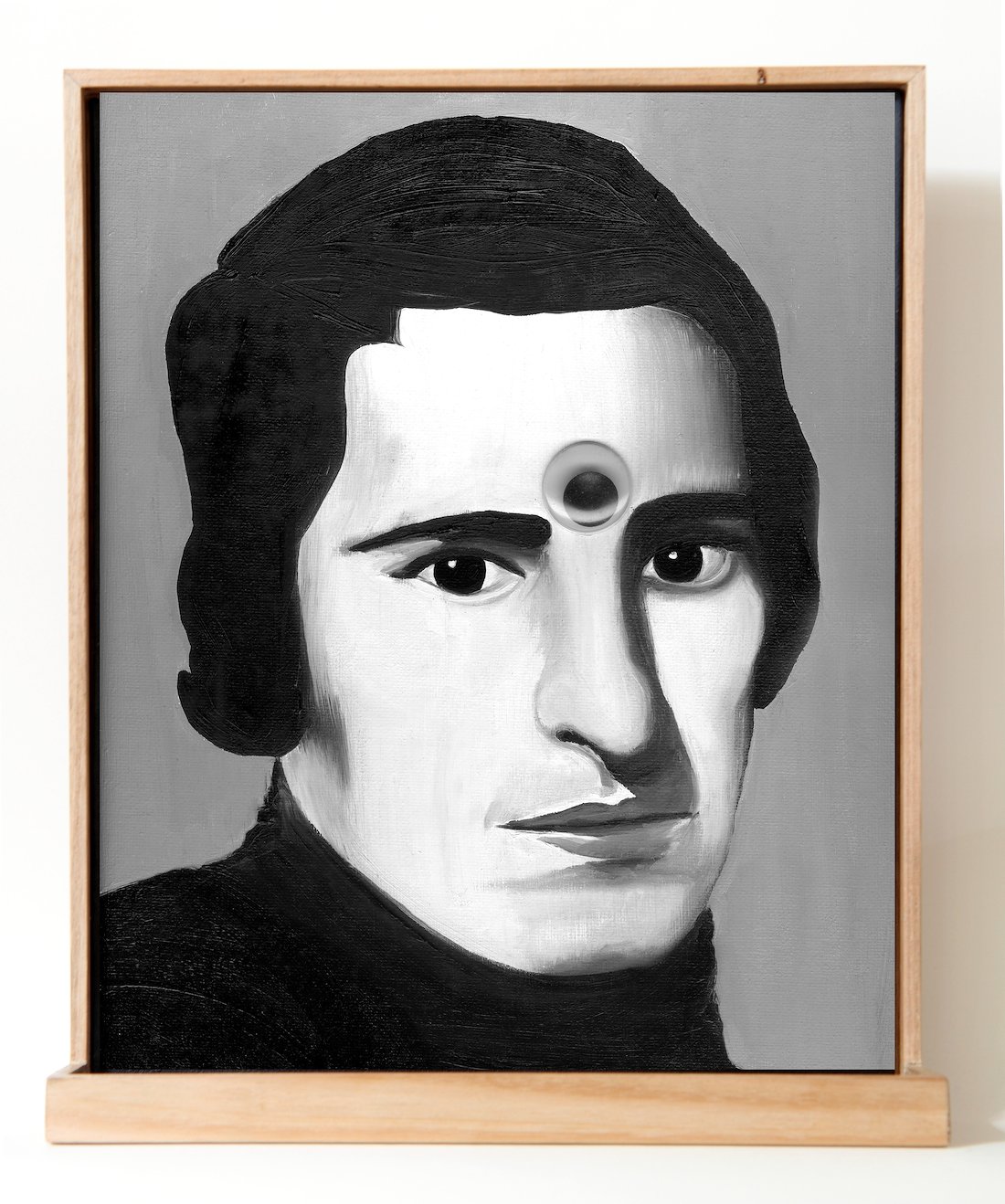

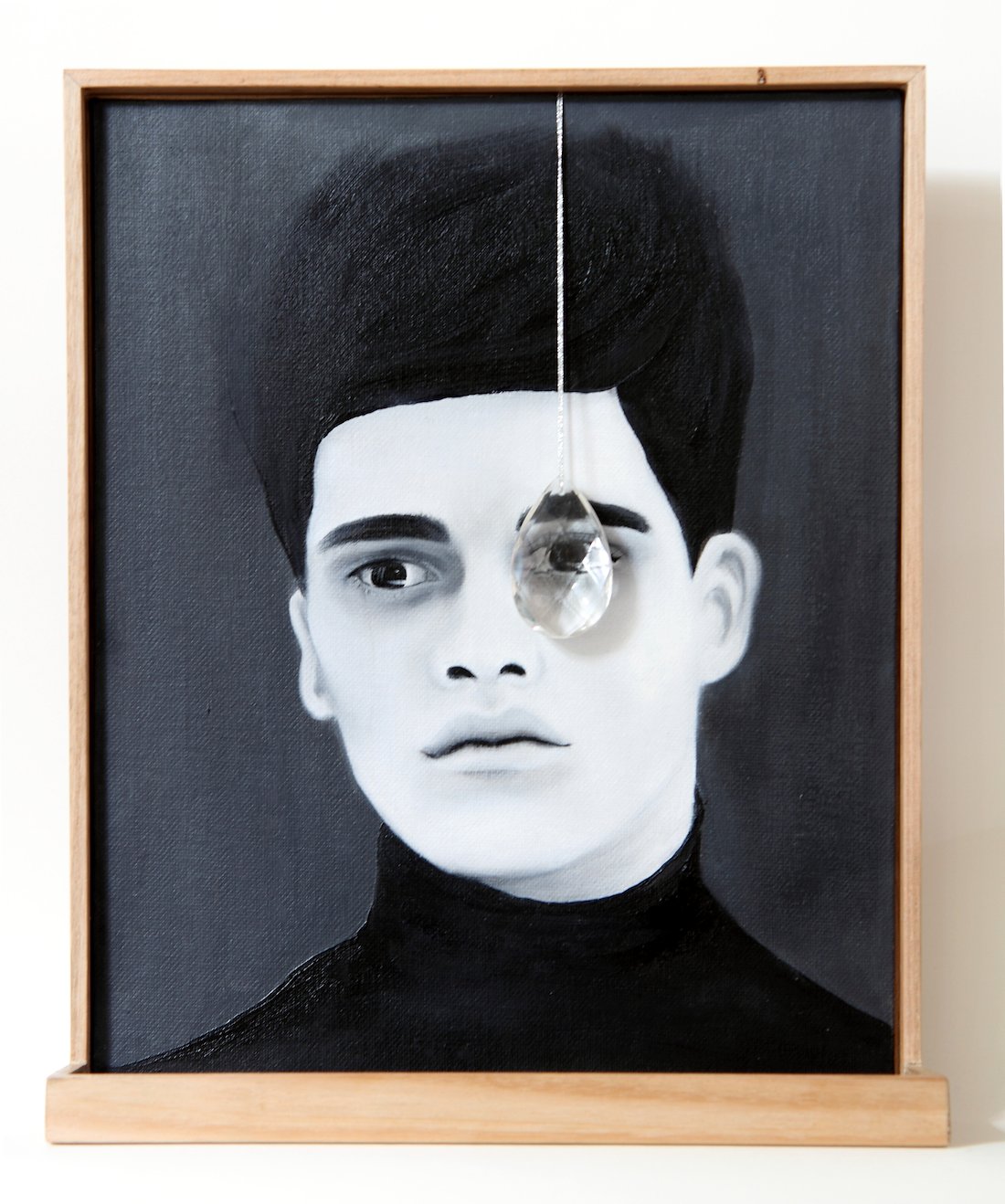

Veronica Kent’s Cloak (2011), which depicts the image of a sleeping child watched over intently by a female figure, represents a similarly complex relationship between child and mother, and childhood innocence and adult responsibility. As in Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience, in Kent’s Cloak, the relationship between mother and child appears at first blush one of static contrast: the roles and distinctions between child and mother are clear. However, the portrait of the mother within Veronica Kent’s Cloak (2011) is in fact a complex work in its own right, a self-portrait titled Visor (2011). In Visor, the subject’s eyes are under-painted white, making way for an unblinking third-eye that is focused on the sleeping child. The colourful cotton tassels that form the eyelashes of the eye are a nod to the tennis visor that Kent remembers her own mother wearing when playing tennis when she was a child. Thus, mother’s eye is shaded by an allusion to her own mother, rendering her a child again, and revealing the fragility of seemingly fixed social categories.

Although Veronica Kent’s solo work is distinct from The Telepathy Project she collaborates on with Sean Peoples, there are some common concerns shared by both practices, including love and intimacy. In a recent presentation on her PhD research, Kent discussed the interaction between love, telepathy, and her art, and referred to an article she had read about the family of Britt Lapthorne, the young Australian backpacker who was murdered while backpacking in Dubrovnik. In the article Britt Lapthorne’s mother described the ache of ‘not knowing instantly’ that something had happened to her daughter despite their distance, and her horror at the knowledge that they had lived in a state of obliviousness for six days while their daughter’s body floated in the sea. Kent notes how this tragedy was amplified by guilt that the love bond had not facilitated a type of telepathic communication, the guilt perhaps stemming from a commonly-held notion that loving someone means that you ‘just know’ when the other is in pain, a belief attributed to mother-child relationships regularly. The mother’s gaze conveys a mix of adoration as well as a desire to protect the child from prospective dangers and disappointments even when she is physically absent. Indeed, the iconography of the third-eye extends the associative reach of Visor.

The conflation of various mediums and materials—photography, painting, and fabric embellishment—reflects the permeability between the various familial and societal roles depicted. The handling of mediums in Cloak can be distinguished from works such as Kent’s Clown Transfer #1 and #2 (2010), which shows, in one frame, a black-and-white illustration of a clown holding a hyper-colour Frisbee-like disk. The image is incredibly striking for the fact that two different registers are compressed into the same visual field through the use of a flatbed scanner. In contrast, in Cloak each medium occupies its own material space and has been able to literally retain its own dimension. The work is therefore tactile, allowing the biographical and emotional strata their own visual plane.

Intimacy, for Kent, can be described as ‘meanings made between separate things,’ and her work explores intimacy between separate visual and material registers as much as the intimacy between the women, men and children in her prints and paintings. In Cloak we see representation of archetypal figures that is at once a tender family portrait, showing the fluidity between the states of childhood and adulthood, and underlining the precarity of Blakean “innocence”, being as it is entirely reliant on others to preserve it.